The textile industry was brought to America in the 19th century from England. But the apparel industry is an American creation at the turn of the 20th century in the Greater Boston area by Jewish tailors, who engineered dressmaker patterns into patterns for mass production . Prior to their efforts, in the 19th century, garments were made individually for each woman by dressmakers who went to each woman’s home. These Jewish tailors became aware of some

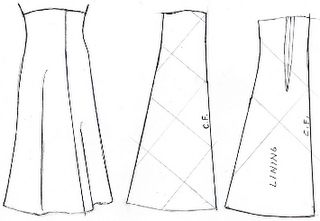

commonalty in the shaping, fitting and making of garments, and production pattern making was born, one pattern to fit more than one woman. They developed a mathematical sizing system to accommodate most women with very few patterns. As businessmen, interested in lowering costs, they continued developing these patterns to become paper “information systems” engineered to control quantities of exact reproductions in cutting and stitching clothing in mass production systems.

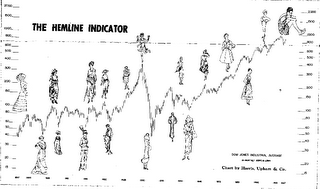

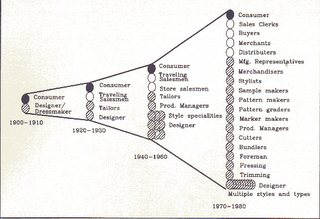

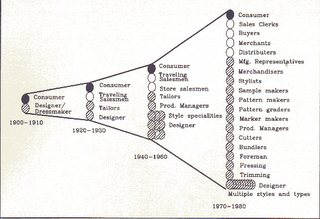

The apparel industry grew from these tailors/businessmen, as they built manufacturing factories for production, which pattern engineering accommodated. The chart above was drawn for my National Science Foundation grant report, 1991, “A 3D-4D Computerized Model for Human-Machine Integration in Apparel Manufacturing Engineering”, to show the

“Fragmentation of Designer and Maker Skills, Distancing Them Further and Further from the Consumer”. Pattern engineering grew a great industry in the early and mid-20th century. But, by the end of the century, our great American apparel manufacturing industry began to fade. My personal belief is that it was much less, going south and then overseas for production, and rather these “old hat” manufacturers inability to change. They were stuck on both style and production

sameness, the foundation of mass production, in order to keep costs low. As a result, they never knew, nor listened to consumers for any of their needs, and consumers are less satisfied. My grants researched ways to do “mass-produced” custom (and later “mass-customization”), computer technologies that could make consumers an integral part of a “future fashion apparel industry system”. Unfortunately, I was ahead of my time in the early 90s, and even the apparel industry’s CAD-CAM vendors, took parts of my ideas, but they too, were unwilling to change. (Perhaps I will tell some interesting stories about these vendors, later.)

Pattern making was first taught to “apprentices” who were called “designers” in the Boston area. Creative designers of styles in America didn’t exist in the early 20th century. Americans were “copyists” or interpreters of the creative ideas coming from Paris ever since the 18th century. Later some designers created booklets for teaching these systems mathematically – that came to be called “pattern drafting”. In the 1940s, when 16, I was old enough to work in these factories as a stitcher on sportswear, and met some of these pattern designers, whose information was passed to them by the old apprenticeship system. I also learned first hand about mass production systems that made America, and Boston area specifically, so famous for quality/quantity production – a system that in the second half of the century we taught to the rest of the world. (Another story later of my experiences in the 1960s that validates this.)

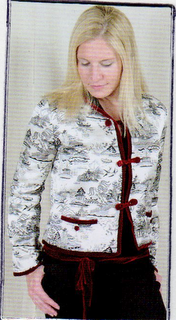

It was in the 1950’s, graduating from college and working in the design rooms of New York, that I learned a sad truth about fashion schools and colleges. Teachers were primarily “dressmakers” and emulated the Paris couture system – and they taught this to other teachers, becoming a narrowing circle of knowledge and experience. So, an even more extreme distancing from the consumer was taking place in the education of young designers for the industry. All workers hired in design rooms were taught in these schools, not as an apprentice in manufacturing, experience that taught critical production knowledge. I easily excelled way beyond them with a technical pattern expertise learned from my own experiments as a teenager coupled with the knowledge of stitching in production. Creators of high fashion styles today make “First Patterns”, which they spend endless time redoing for quality, but never preparing for production. While creating high fashion styles my First Patterns were “Engineered Patterns” to immediately reproduce creations into ready made garments for cost-effective manufacturing. A positive effect from these fashion schools is that America began producing more creative designers, but the negative effect is an ever widening gap between creative design and pattern engineering. (Click the “Wall Between Design and Manufacturing”) By combining great creativity with unequaled technical expertise, I became extremely successful as a designer and manufacturer of high quality designer clothing at low cost, selling nationally to all the top retailers from the 1960s to the early 1980s. . One driving point I continue to make in my grants and to students is that decisions of marketing and production, costs and quality must be made at the “Point of Design” (P.O.D., another chart I will post soon).